In the introduction to Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan recalls an editor’s lament upon first reading his manuscript for the book:

‘Seventy-five percent of your material is new. A successful book cannot venture to be more than ten percent new!’

But McLuhan nonetheless pressed on with his majority-new book, in his estimation, “a risk [that] seems quite worth taking,” and published one of the most weirdly, perpetually prescient books of the twentieth century.

Majority-new. How many fashion designers can lay claim to creating something so unprecedented, the bulk of its constituent parts and processes are themselves novel? Something—be it a garment, a collection, a brand, a business model—that’s seventy-five percent new, along all available axises? Forty-five percent? Thirty, even?

Surely, very many of them. Most, perhaps? After all, fashion, one commonly assumes, is the domain of the new:

‘The job of fashion and art is to be froth—quick, irrelevant, engaging, self-preoccupied, and cruel. Try this! No, no, try this! It is culture cut free to experiment as creatively and irresponsibly as the society can bear.’1

And maybe this is true of “fashion” more broadly, in the bleeding-edge-of-cultural-production sense of the word.

But in the strict sense—clothes—not a single brand or designer has fully reckoned with the scope and force of what’s possible, nor are they retooling themselves towards this potential:

Most brands remain encumbered by capital-intensive, long-run manufacturing processes that sharply narrow their creative range. Within the dominant industry paradigm, being too creative can kill you. Thus, in order to survive as a business, designers must clip their own artistic wings, and pray to God their “safe” choices sell, rather than wind up on clearance racks, or in bonfires.

There aren’t any designers I’m aware of who are innovating not only with the designs of their clothes, but also with the means by which they design in the first place. No one is seeking to build, for themselves and for others, an entirely new medium of design, a purpose-built tool for thought that could augment their creativity tenfold.

Few designers are harnessing recent advances in generative artificial intelligence in any significant way; fewer still have the means to feasibly shape their results into physical realities.

Very few designers, perhaps only higher-ups at the largest of houses, are able to exercise one-hundred-percent creative control over the design of their garments’ trims. Due to sourcing costs and difficulties, off-the-shelf zippers and shank buttons are tolerated as a fact of life.

The shift to e-commerce, and promise and power of the direct-to-consumer experiences, have largely materialized as a race-to-the-bottom. And while a few tech-leaning firms have pioneered innovative methods of distribution, seemingly, or in at least one case, explicitly, at the expense of sartorial novelty.

To this day, the point of sale remains the point of termination for the lion’s share of brand-customer relationships. Despite a years-long craze over “ownership,” where obscure cryptography algorithms managed to work their way into the zeitgeist of the fashion industry, there are still no new ways of owning clothes that feel non-extractive to consumers, let alone worthwhile and engaging.

No existing brand is verifiably sustainable, through-and-through. Fast-fashion’s sins in this regard are legion, and well-documented. But even brands the purport to be “conscious” in regards to sustainability offer mostly marketing smarm and fig-leaf initiatives. They can’t quantify the environmental effects of their entire supply chain. They can’t assure you completely that some kid chained to a desk didn’t sew your sweatpants together.

There is nothing new under the sun. Brand “collaborations” proliferate like Marvel sequels, seeking to magically multiply the surface area of profitability for all parties involved without actually creating anything new, like cheapskates at a vice squeezing the last atoms of toothpaste out of a tube. Very few brands are actively forging new stories and making new meaning.2

Season after season, the latest crop of wunderkinds pump out inspired collections, but for houses not in their name, and at the behest of shareholder profits. Very few have both the talent and the wherewithal to helm their own house; fewer still to ascend to the pinnacle of “face of the brand.”3

…and of course, there certainly isn’t a designer with a brand who’s working on all of these areas, all at once, is there? Well, there wasn’t…

Until today.

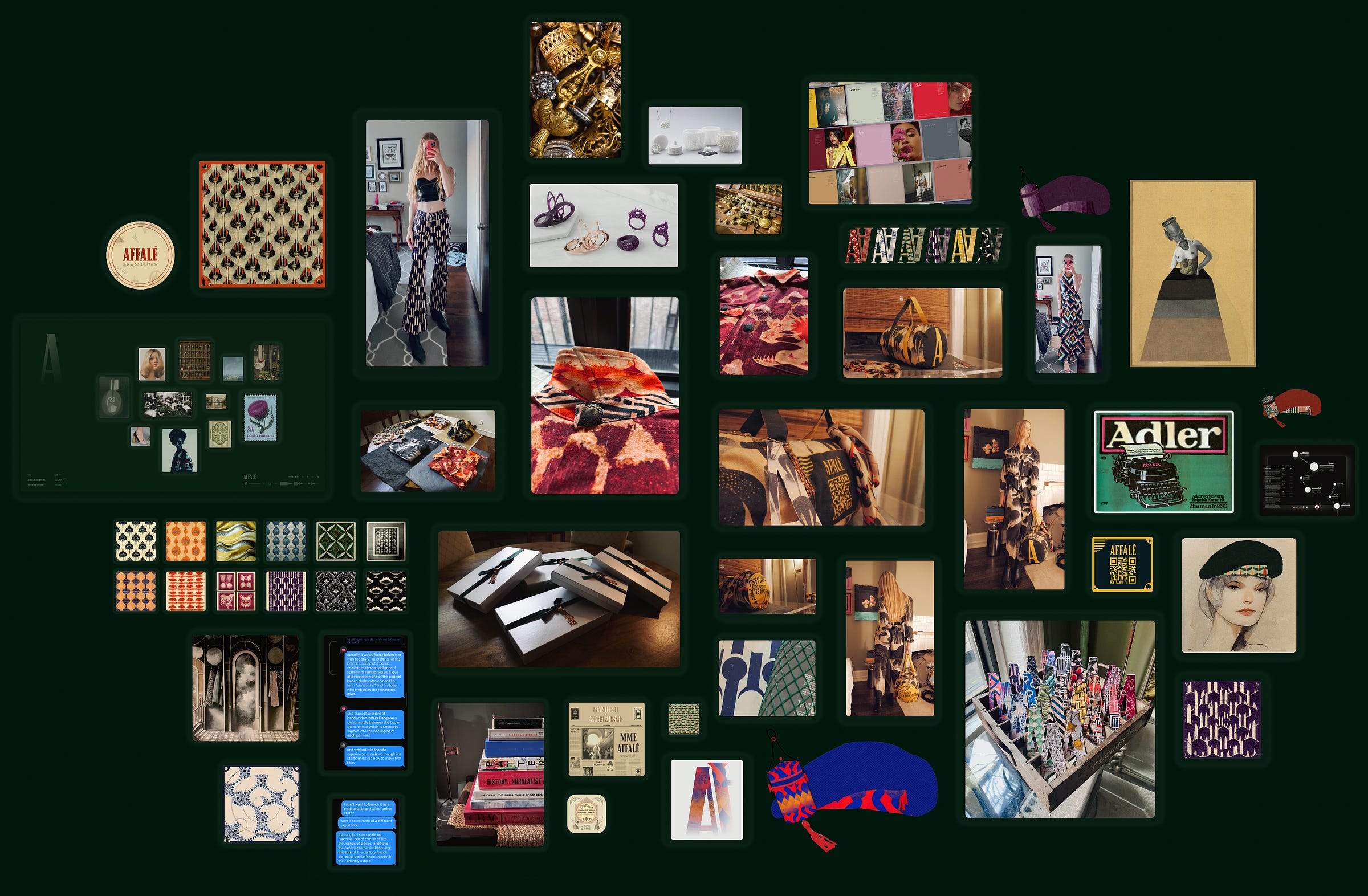

Introducing AFFALÉ, A Brave New Brand

Hi! I’m Jane Flowers, and I’m so excited for you to meet my new brand, AFFALÉ! We’ll get to know each other soon enough—after all, I’ll be chronicling every step of my journey as I build this brand into something really special. More than any other brand, AFFALÉ is fashion’s future.

In the coming weeks, as I officially start work on the brand, I’ll publish pieces that elaborate on each of my “brand pillars,” and detail my early efforts with each. As I described to one friend, they’re my “Nine… just nine…” Theses. Perhaps I’ll end up nailing them to the doors of Vogue, one fine day in the future, but for now, they are:

A No-Inventory Operating System

A New Medium For Fashion

AI Textile Design

3D Printed Trim

A New Storefront

New Patterns of Ownership

Verifiable Sustainability

A Fairy-Tale For Adults

At The Helm, As The Face

You’ll also learn what “AFFALÉ” means, read about my five-year journey in the fashion industry to reach this point, and lots more. Stay tuned! Much building lies ahead. I’m so excited to have you on this journey with me!

plus chic, tu meurs,

—jane

Or McLuhan, again:

‘Of course, there is much zest of novelty in this cult [of fashion], and the eventual equilibrium among the senses will slough off a good deal of the new ritual…’

As I sat in a coffee shop in downtown Manhattan, writing this very piece, I happened to overhear a conversation between two thirty-something venture capitalists at a neighboring table. They were earnestly hatching a plot to purchase the rights to a vintage French label, defunct for over a century, and slap the branding on imported home goods manufactured by, “the same guys that make all of Parachute’s shit.”

Of course, most of the leading womenswear designers are men—rendering their potential to serve as the brand’s avatar moot anyways. Is it any wonder why designer clothes feel less and less supportive of the woman who actually wears them?